There are years when the world feels like it has been placed in the hands of people who shouldn’t be trusted with a toaster, let alone with history. Me included. Sometimes my own life feels like it shouldn’t have been entrusted to me.

Headlines in the papers. Bills in our mailbox. Suffering on sidewalks and in our families. These daily dares challenge us to stay reasonable inside the unreasonable, calm while the house is on fire, and loving as love is mocked.

This particular kind of year has an additional texture. We are made to live inside an inordinate amount of information and the strange intimacy of AI. It’s not just “news,” but the constant, frictionless availability of explanations for everything. Synthetic confidence. The feeling that meaning is being produced for us faster than we can metabolize the experience.

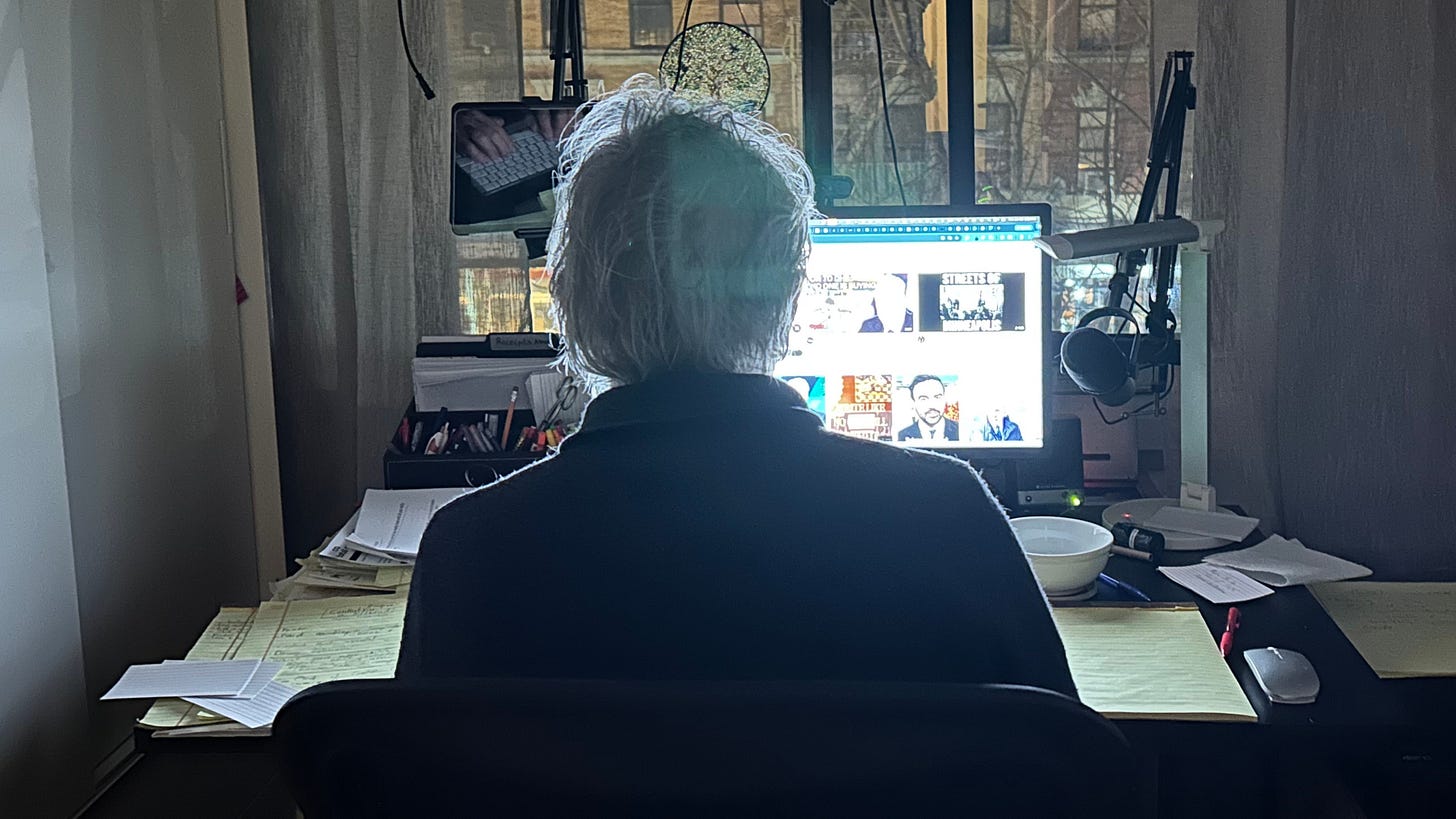

So, I scroll at 11:47 pm, the ache at the top of my skull, and the sound of notifications landing like pebbles.

And yet.

New and better stories are being born in places invisible to us, like stars that are still too tender for our eyes to recognize. As our disoriented hearts grieve the myths that are dying away from our sight, new ways of being present to each other are being discovered and practiced in thousands of communities of young, old, divergent, and inexplicably good humans, in classrooms, back porches, and midnight phone calls.

If you can feel that at all, even as a faint signal, then you already know you’re part of it.

The Fire and the Screen

Let’s turn to something embarrassingly ordinary: the glow of your screen. You open one tab on your browser. Quietly, you open another. Then another. Soon, your mind is living in a crowded hallway of possibilities. One tab offers learning. Another, entertainment. Another danger. In this environment, we look for ways to process our fear, grief, and sorrow, three unmistakable signs of holy ground where being fully alive matters more than happiness.

With the screen casting light on my face, I notice my hand resting on the mouse, like it’s a steering wheel, realizing this isn’t steering, this is bracing.

Some evenings, I stare into the screen and feel like I’m splintering. Anxiety in the chest, a tightness behind the eyes, the urge to find one more video from someone who gets it, to give me some modicum of certainty about the future. Oh, screen, give me something, anything, please!

This whole experience of gathering around light started a long time ago. About a million years ago, we invented fire. 780,000 years ago, we began cooking. As a result, more food and energy became available just in time when our brains were growing and needed more energy to keep going.

The miracle of cooking was not only nutritional. It was existential. We were no longer required to chew all day, to live in a continuous state of procurement and urgency. We could sit. We could sit and stare into the flame. We could hear ourselves think. With the aroma of smoked meat, and hush after chewing stopped, and with enough protein, fat, and carbs in our systems, we could experience something that later civilizations would treat as a problem to be solved, but which was actually the first doorway to human creativity: boredom.

Blessed boredom.

Around the fire, boredom did what it always does when it’s not annihilated by noise. It made us perplexed. Give a human being enough time, and eventually, they will turn from grunting and scratching to asking questions. Who are we? Why are we here? What’s going to happen next?

According to our ancient texts, God didn’t scold the agony of human self-discovery. He put that tree of knowledge in the garden, fully expecting us to eat from it. God blessed us, “Perplexed, huh? That’s good. Go on. Enter the unknown.”

Around that fire, we discovered two powers that have never left us.

The first is presence, the plain, startling awareness of being here in a world that is happening right now.

The second is story, the equally plain, equally startling awareness that we can remember the past and imagine the future.

Presence and story.

The first two tabs we humans ever opened.

If you strip away the obscure and sometimes exhausting teachings about spiritual growth and complicated modern theories of human development, much of it comes down to learning to live within these two capacities without letting either become a prison.

Over time, civilizations turned these two capacities into two essential spiritual teachings. The Eastern tradition asks, “What is real?” It pursues direct experience, inviting us to pay attention to what is arriving through the five senses, thought, and emotion. Stories, on the other hand, are not really real.

It treats the meaning of existence as something communicated through practices such as sitting and breathing, and through the experience of whatever else happens to happen, rather than through explanations.

I discovered this about fifteen years ago when I signed up for an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction class. During those weeks, we spent a comical amount of time on tiny things, like feeling your hands on your knees, feeling the breath enter your nose, and noticing how your mind runs from silence, as if it were a predator. Later, I got apps and amassed what I can only describe as a ridiculous number of hours of meditation.

Time well spent.

It helped me learn something both simple and profound: I can return to being here. This was never a perfect practice, and sometimes it was dismal. That didn’t matter. I could always come back to the simple fact and the permission to speak to the intimidating God who famously said, “I am,” with my own “I am.”

By contrast, the Western tradition asks: “What is good?” This tradition seeks meaningful participation in a story, treating life as something that requires imagination, purpose, and continuity. We tell ourselves and each other stories—not out of sentimentality, but because, without stories, our days would be a mere collection of particles flying around. Story is how we make our lives cohere. Narrative is how we find our place in a larger whole.

When you renew your story, you renew reality.

There’s a reason these two “modes” feel so distinct. Our brains are wired with a polarity that echoes this historical split. There is circuitry for direct experience and circuitry for narrative explanation, and the two work inversely. Like a toggle. When one becomes active, the other quiets.

You don’t have to master the brain map to understand this. You feel it every time you try to listen to someone while simultaneously preparing your answer in your head. We can’t fully do both.

To listen, you have to trust the moment. And to trust the moment, you have to trust the world. And to trust the world, you have to have a story.

When One Tab Becomes a Trap

This is the part where presence becomes difficult for the exact reason it’s valuable. When you start practicing presence, it can be painfully boring. You sit down, you try to watch your breath, and your mind behaves like a small animal being cajoled into a cage.

The body grows restless. The jaw tightens. The mind tempts you with errands, memories, grievances, daydreams, and a sudden desire to reorganize your kitchen pantry. Anything but this.

And then, if you stay, things get worse. The silence stops being empty. It becomes crowded with everything you’ve been avoiding. The shamed part of you. The grieving part. The part without a plan.

Presence is contact with what is.

Presence is about honesty.

It’s why I love asking people I coach the simplest question with terrifying sincerity: How does it feel to be you?

I once asked my wife that while we were on a road trip, and she answered, “It just feels.”

Exactly.

There are no words for the raw feeling of being alive. Words arrive later, and when they arrive too fast, they interrupt. They turn life into a story about life. They replace the lived with the narrated. And since I can’t do both at the same time, the moment I engage with the story about me, I cannot be me. It’s akin to one of the ancient wise men’s sayings, “I know God, until you ask me about God.”

And here comes the twist: Presence is not enough. If presence becomes only an exercise in accepting your circumstances without allowing your imagination to attach itself to a story and alter your life, it becomes a security guard of the status quo. Since the Big Bang or since God’s water broke (depending on your story), reality is in motion. Presence can make you calmer but not necessarily more alive. It can shrink your cognitive pupil from living in what shamans call “the whole time” to the mere present.

There’s more to life than the present moment.

There’s a story, many stories actually, and they are not optional. We are part of a world that is made of stories.

Meditation will not move a mountain.

Story will.

If enough people tell a certain story, they will organize themselves, gather tools, dig, build, destroy, liberate, colonize, heal, and invent. Story creates reality. “In the beginning was the word,” the old text says.

Even if, like me, you’re not religious, you know what these texts pointing at: words don’t just describe the world. They summon a world.

And because the story is so powerful, the story we tell ourselves can become our captivity, an old, tired path we keep walking because we do not know how to step outside of it long enough to have a new experience.

That hat no-story space of presence, that moment of detachment, is precisely where a new story can be born. Presence is an always-available clearing in which the nervous system stops rehearsing the current story.

When we are constrained by our story and feel like there’s a wall between us and the world, presence makes us available again. For a larger store, or a smaller one, or the one that is more true.

Presence is a delightful boredom that allows us to imagine something different and to dare to change the world through art, revolution, discipline, and fierce love for ourselves, for another, or for our vocation.

Epic and Ordinary

Religion is a God-management system. Politics is an influence-management system. An economy is a stuff-management system. In reality, all systems are story-management systems.

We come together, whether in person or through our screens, to help each other be present to it all, to encounter ordinary life in the here and now, and to remember that there is a larger story in which we all belong to each other and to the world.

We come together to be enchanted with stories old and new, to give, to grow, to restrain ourselves, to learn how to know, to learn how to not know, to be astonished, to find ourselves in the stories of others and find them in ours.

Presence and story are AI-proof skills of the future. They are two human capacities that are unoutsourcable to AI or whatever comes next. No machine can do your living for you, and no stream of information can bring your new story to life.

Presence and story are how we become less capturable by outrage, less manipulable by propaganda, less lonely inside our own heads, and more capable of the kind of connection that can carry us through social, political, and relational trouble ahead.

“Do not be afraid of life,” William James wrote.

The question then arises, “Where do these two capacities meet?” Historically, traditions have named that overlap “mystical experience,” when the whole mind and body light up and both neural circuits fire--being fully in the here and now while in the ecstasy of a story.

We are often told that mystical experiences are for special people. You know, mystics. And that we mortals have access to those states about twenty seconds or—in the most generous estimate—twenty minutes per year.

This framing misses something.

It bypasses ordinary life.

It misses cooking the dinner, cleaning the house, paying the bills, playing with kids, talking with friends, rolling a cigarette, knitting, births, deaths, and every single experience in between. We are allowed—nay, invited—to be fully present to and enchanted with it all.

We are still around the fire, but this time it is not a tribe, but whole humanity, gathered around the internet, looking at our screens, wanting to tell each other, “I’m here now. This is my story. Tell me yours. Maybe we can find, or be found by, better stories in which we belong to each other.”

Does this seem too simple?

Allow yourself to be seduced.

The other world is in this world, and the ordinary is the secret of the divine.

Presence and story are not exotic techniques hidden in the ancient pages or captured and dispensed via techno-futurist apps. They are stem-cell capacities each one of us already has. We know them.

The question is whether we will use them until they become strong enough to carry us into a larger life together. We have done this before.

You don’t need a new personality to meet this difficult moment. You don’t need a perfect plan. You don’t need to be in control. You already have what you really need.

Presence and story—a warm mug of tea in your hands and a keyboard awaiting you to write something true and kind, and press send.

I always love to know what you think. Let me know below… 🙏🏼

This was beautiful, Samir. And resonant for me. Thank you for being.